Table of Contents

This page gives a quick overview of G3D for new users.

For information on how to install G3D on your system and compile your own projects that use G3D, see the Installing G3D page for your operating system linked from the title page.

To get started quickly, refer to the samples/starter starter project for a small example program of how most people use G3D. On Unix-like operating systems, just run 'icompile' with no arguments to generate your own G3D starter project.

Customizing Rendering

G3D provides several layers of access to the renderer. The most abstract level allows G3D to manage all of rendering for you, providing a data driven model for managing scene-graph level objects (like G3D::Scene, G3D::Model, and G3D::Entity). This is convenient if you are innovating on modeling, simulation, gameplay, networking, or post-processing and want an out-of-the-box rendering system. Using highly abstract techniques also is relatively future-proof, because future versions of G3D are likely to use similar APIs but optimize them for then-current hardware.

The next level down (G3D::Renderer) gives you access to the rendering class that consumes the scene graph. You can add or modify render passes by subclassing the renderer and overriding the relevant shaders.

The most concrete level (G3D::RenderDevice) gives you complete control over the rendering system. This allows you to innovate further with shading as well as surface determination, stylization, and materials.

You can even go below the G3D::RenderDevice level and make your own OpenGL calls. In this case, you must manage state yourself to avoid confusing the higher level abstraction.

These levels of abstraction are explained further in the API Index. Here is an order in which you might begin your G3D project, working down the levels of abstraction as necessary:

- Create your own .Scene.Any data files to work within the provided G3D system. Choose the value of G3D::DefaultRenderer::deferredShading based on the number of lights and meshes.

- Subclass G3D::Surface if you need to create a new kind of geometry, such as dynamic procedural geometry on the GPU. Usually one creates a G3D::Model subclass to enable the new Surface to work with G3D::Scene.

- Subclass G3D::Renderer if you want to modify the style of OpenGL-based rendering. For example, to implement a new kind of tiled-deferred rendering.

- Override G3D::GApp::onGraphics3D if your rendering requires a different style of API than G3D::Renderer provides, such as a ray tracer.

- Override G3D::GApp::onGraphics if you need complete control of both the 2D and 3D rendering methods.

Often you can use the existing classes but make modifications to local versions of the UniversalSurface and UniversalMaterial GLSL shaders. The corresponding classes will load the shaders from a local directory before the installed G3D directory. Macro arguments, which can be passed through from data values set on UniversalMaterial and ArticulatedModel::Pose inside a .Scene.Any files, are an easy way to flag particular objects for special processing.

Frameworks

Every application needs a framework that manages events, provides a command-line or graphical user interface, and initializes key subsystems like OpenGL and Winsock.

G3D::GApp Framework

Small games, research projects, and homework assignments are written on short shedules and have moderate GUI needs. The G3D::GApp class is designed to get such projects running quickly and easily.

See the samples/starter project for an example.

G3D::GApp will create a window, initialize OpenGL, create a log file, and provide you with framerate, video recorder, camera and tone map controls, and a debugging user interface. It works exactly the same on every platform, so you can write once and run anywhere. By subclassing it you can override methods to respond to various high-level events like keypresses, rendering once per frame, and processing input from the network or simulation.

You can create most standard Gui elements using the G3D::GuiWindow and G3D::GuiPane classes and tie them directly to existing methods and variables. G3D::GApp handles the event delivery and rendering of these elements.

Within GApp you can choose to write explicit immediate-mode rendering code that sends triangles to the GPU every frame; rely on the G3D::Surface, G3D::Surface2D, and various model classes like G3D::ArticulatedModel for retained mode (scene graph) rendering, or mix the two as demonstrated in the starter project.

G3D::RenderDevice Framework

G3D::RenderDevice provides immediate mode rendering for G3D::GApp, but you can also use it directly yourself. Creating a G3D::RenderDevice automatically intializes the GPU, makes a window, and loads all OpenGL extensions. You can then write your own main loop and issue explicit rendering calls. For event delivery and a managed main loop, see G3D::OSWindow, G3D::GEvent, and G3D::UserInput.

OpenGL Framework for Teaching

If you are using the GApp framework you can skip this section.

G3D provides a lot of support and removes most of the boilerplate of 3D graphics. For most people, this is desirable, but if you are teaching a 3D graphics class you may want your students to experience raw OpenGL before making it easier. You can use G3D to intialize OpenGL in a platform-independent way and then have students write their own OpenGL calls (in fact, you can always mix OpenGL and G3D calls, no matter how sophisticated the program).

See the samples/rawOpenGL project as an example.

A sample progression for a course is to begin with raw OpenGL as in the example, then add the linear algebra helper classes (e.g., G3D::Matrix3, G3D::Matrix4, G3D::Vector2, G3D::Vector3, G3D::Vector4), event handling (through G3D::UserInput, initialized off the G3D::RenderDevice::window()), and mesh loading via G3D::IFSModel.

Once students understand the basics of rendering in OpenGL you can introduce the G3D::RenderDevice methods that make OpenGL state management easy (note that RenderDevice follows the OpenGL API) and work with advanced classes like G3D::VAR, G3D::OldShader, and G3D::ShadowMap which abstract a lot of OpenGL code. When students are ready to make highly interactive projects, possibly as final projects, introduce G3D::GApp so that the application structure is provided.

In addition to real-time 3D, G3D provides good support for ray tracing and computer vision in an introductory class. This allows you to address multiple topics using the same set of base classes so that students do not wast time adapting to new support code for each assignment.

External Framework

If you are using the GApp framework you can skip this section.

Major commercial projects, expecially ones where G3D is being added to an existing codebase, may require a different application structure than GApp provides. You can either connect directly to your operating system's windowing system or a 3rd party GUI library like wxWidgets, FLTK, QT, or Glut. In such an application, the non-G3D framework creates the windows and G3D renders inside a client window that you designate.

When using an external framework you must explicitly create a G3D::OSWindow that represents the operating system window into which you will render. How you do this depends on your choice of external framework. For any framework on Windows, you can use the G3D::Win32Window subclass and initialize it from a HDC or HWND. User-supported G3D::OSWindow subclasses for many popular windowing packages like wxWidgets are available on the internet. If you are not on Windows and are using an external framework for which there is no published package, you must subclass G3D::OSWindow yourself and implement all of its pure virtual methods.

Once you have a G3D::OSWindow subclass object, construct a G3D::RenderDevice. This is the interface to OpenGL rendering. You may also wish to create a G3D::UserInput, which gives polling access to the keyboard, mouse, and joystick.

In your rendering callback (which is determined by the external application framework), place rendering calls between G3D::RenderDevice::beginFrame() and G3D::RenderDevice::endFrame(). This constructs an image on the back buffer–to make it visible you must invoke G3D::OSWindow::swapOpenGLBuffers().

G3D as a Utility Library

If you have already chosen a framework you can skip this section.

Some features in G3D are useful to any program, regardles of whether it performs 3D computations or runs on a graphics processor. These include the platform independent G3D::Thread and G3D::Spinlock, data structures like G3D::Array, G3D::Set, G3D::Table, and G3D::Queue that are both fast and easy to use, and the G3D::System class that provides fast memory management, timing, and CPU information.

When using G3D as a utility library no GUI framework is necessary. To support utility usage, the library is split into two pieces: G3D.lib and G3D-app.lib. All event-handling, windowed, and OpenGl code is in the G3D-app.lib portion. This means that you can use G3D.lib without linking against OpenGL or setting up an event handling routine.

Conventions

Coordinate Systems

RenderDevice uses separate matrices for the object-to-world, world-to-camera, perspective, and Y-inversion transformations. The concatenation of the first two is the equivalent of the OpenGL ModelView matrix; the concatenation of all of these is the OpenGL modelview-projection matrix.

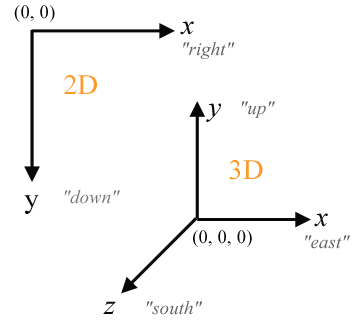

The default 3D coordinate system is right-handed with Y=up, X=right, and Z=towards viewer.

Objects "look" along their negative z-axis. G3D assumes a compatible "world space" where Y=up, X=East, and Z=South.

The default 2D coordinate system (for 2D clipping, textures, and viewport) has the origin in the upper-left, with Y extending downward and X extending to the right.

Following OpenGL, (0,0) is the corner of a pixel/texel; the center location is offset by half the width of a pixel/texel.

The texture map origin is at the upper-left. This means that when rendering to a texture, screen pixel (0,0) in 2D mode corresponds to texel (0,0), which is convenient for image processing.

Because the G3D 2D and texture coordinate systems differ from the underlying OpenGL ones (and match DirectX conventions), RenderDevice applies an extra transformation that inverts the Y-axis when rendering to a texture. This inverts the winding direction, so the front- and back-face definitions are also reversed internally by RenderDevice. This is only visible in that G3D::RenderDevice::invertY will automatically be set and that the g3d_ProjectionMatrix differs from the gl_ProjectionMatrix in shaders (note that OpenGL has deprecated gl_ProjectionMatrix as of GLSL 1.5).

Inside a shader, gl_FragCoord.xy is the window-system coordinate; it ignores the viewport, projection matrix, and scissor region. G3D arranges shaders such that its origin is at the top-left.

Memory Management

You can allocate memory for your own objects as you would in any C++ program, using malloc, calloc, alloca, new, and heap allocation. In addition, G3D provides System::malloc, System::alignedMalloc, and a reference counting garabage collector that you may choose to use. G3D::System's memory managment is faster than the provided C++ runtime on many systems and the reference counter is easier to use.

Internally, G3D uses reference counting to automatically manage memory for key resources, like G3D::Textures. These classes are allocated with static factory methods (G3D::Texture::fromFile) instead of new and pointers are stored in Ref types (G3D::shared_ptr<Texture> instead of G3D::Texture*). You can use the Ref type as if it were a regular pointer, sharing a single instance over multiple Ref's, dynamically casting, and invoking methods with the arrow (->).

Reference counted objects automatically maintain a count of the number of pointers to them. When that pointer count reaches zero the object could never be used again, so it automatically deletes itself. This is both convenient for objects that have no natural "owner" to delete them. It also helps avoid memory leaks because memory management is automatic.

If a class subclasses ReferenceCountedObject, never create a raw pointer to it and never call delete on an instance of it. |

You can create your own reference counted classes using:

class MyClass : public G3D::ReferenceCountedObject {

protected:

MyClass();

public:

static shared_ptr<MyClass> create() { return shared_ptr<MyClass>(new MyClass()); }

...

};

Traits

G3D uses a C++ convention called "traits" for separating the properties of some objects from the methods on their classes. This is useful for cases when you need an adaptor to tell one (usually templated) class how to work with another one that wasn't designed in anticipation of that cooperation. For example, say that you have a class called Model that you'd like to use with G3D::Table. G3D::Table is a hash table, so it requires a function that computes the hash code of any particular Model, yet Model wasn't originally written with a hashCode() method.

The solution is a series of overloaded templates. There are currently four different kinds of these, and they are outside of the G3D namespace (since you'll be writing them yourself). An example is more explanatory than the specification, so here are examples of the four. You only need to define the ones required by the classes you are using, like G3D::BSPTree and G3D::Table. G3D provides implementations for many built-in classes, like G3D::Vector3 and G3D::AABox.

For G3D::KDTree:

template<> struct BoundsTrait<class MyClass> {

static void getBounds(const MyClass& obj, G3D::AABox& out) { ... }

};

For G3D::Set and G3D::Table:

template <> struct HashTrait<class MyClass> {

static size_t hashCode(const MyClass& key) {

return static_cast<size_t>( ... ); // some value computed from key

}

};

For G3D::PointKDTree:

template<> struct PositionTrait<class MyClass> {

static void getPosition(const MyClass& obj, G3D::Vector3& p) { ... }

};

For G3D::Table and G3D::Set. The default version calls operator== on a and rarely needs to be overriden.

template<> struct EqualsTrait<class MyClass> {

static bool equals(const MyClass& a, const MyClass& b) {

return ...; // true if a and b are "equal"

}

};

Naming Conventions

All G3D routines are in the "G3D" namespace and can be referenced as G3D::xxx.

Unlike other libraries, there is (generally) no prefix on the routines, since that is the job of a namespace. The G3DAll.h header includes using namespace G3D; so that you don't have to type G3D:: everywhere.

The exceptions to the no-prefix rule are classes like "OSWindow" and "GFont". We ran into name conflicts with OS-level APIs on these classes since those APIs don't have namespaces. It would be confusing to have both G3D::Font and Font classes in a system at the same time, so we opted to rename the G3D classes to have a "G" on the front.

Samples

- A sample is an infinitesmal point on the screen or a surface where light is measured. By default, there is one sample per pixel or texel, at the center. Under MSAA, CSAA, and SSAA rendering there can be multiple samples per pixel or texel.

- A pixel and a texel are a square area of an image (e.g., G3D::Texture or G3D::Image). When using integer coordinates, "pixel" is used. When using normalized coordinates, "texel" is used.

- A surfel contains material information at a sample location on a surface.

GLSL

GLSL structs are fairly limited by the allowed types (e.g., no samplers), are hard to pass consistently across drivers, and can't be used within the preprocessor, where much GLSL programming occurs. So, many G3D routines flatten structs by using groups of variables with common prefixes. Underscores replace periods and double-colons this naming convention. For example, AlphaFilter::COVERAGE_MASK becomes AlphaHint_COVERAGE_MASK.

Transparency

Computer graphics has a specialized but ill-defined vocabulary for subtly different concepts around transparency. G3D uses the following terms with specific meanings:

Partial coverage (alpha) occurs if the geometry covers more area than the actual surface it is modeling. For example, a tree leaf modeled as an alpha-cutout of a simple rectangle. A surface may have partial coverage at a single point (a fractional alpha value) or over the entire surface, where alpha is less than one at some location. Partial coverage can occur across a pixel or a surface. Binary coverage is a special case of partial coverage for surfaces.

Transmission occurs where light passes through areas that are covered, possibly with attenuation or refraction. A transmissive surface may also have partial coverage.

A sample on a surface is opaque when it precludes any radiance contribution from surfaces farther along a sample ray. That is, it must have 100% (alpha = 1) coverage and no transmission.

A G3D::Surface:

- is opaque when all of its samples are opaque (no partial coverage or non-refractive transmission anywhere)

- is nonopaque if some of its samples are not opaque. It describes any situation that could cause two or more geometric surfaces to contribute to the radiance value at a ray sample

- has binary coverage if its coverage can be expressed as 0 or 1 at every point (AlphaFilter::BINARY, AlphaFilter::COVERAGE_MASK) and it cannot be assumed to have coverage=1 everywhere.

- has transmission if any of its samples have transmission.

- requires blending if it has partial coverage that is not binary or has transmission

UniversalSurfaces with refractive transmission but full coverage do not require blending because they write the refracted sample themselves, so are counted as "opaque" by the rasterization renderer.

"Collimation" in G3D refers to 1 - diffusion, i.e., how little a surface diffuses light. It is stored in the alpha channel of the transmissive texture.

STL vs. G3D

In general, we recommend using STL classes–they are standardized and do their job well. However, for some data structures G3D provides alternatives because the STL implementation is not appropriate for real-time or graphics use.

G3D::String, G3D::Array, G3D::Queue, G3D::Table, and G3D::Set are written in the style of the STL, with iterators and mostly the same methods. However they are optimized for access patterns that we have observed to be common to real-time 3D programs, are slightly easier to use, and obey constraints imposed by other graphics APIs. For example, G3D::Array guarantees that the base pointer is aligned to a 16-byte boundary, which is necessary for working with MMX and SIMD instructions. These classes also contain fixes for some bugs in older versions of the STL.

The G3D::System class provides platform-independent access to low-level properties of the platform and CPU. It also has highly optimized routines for timing (at the cycle level) and memory operations like System::memcpy.

The STL now has thread support, but no good parallel for loop or efficient spinlock. Use G3D::runConcurrently for a portable, CUDA-like parallel loop on CPU.

Image Processing

G3D can be used to build image and video processing applications. It provides easy to use CPU-side classes like G3D::Image and the hardware-accelerated class G3D::Texture. The G3D::VideoInput and G3D::VideoOutput classes provide basic support for video processing.

G3D::RenderDevice::push2D puts the GPU in image mode and G3D::Texture::Settings::video selects appropriate image processing defaults. Use G3D::Draw::rect2D to apply pixel shaders to full-screen images for fully programmable GPU image processing.

See the API index for image file format support, Bayer conversion, gaussian filtering, tone mapping, and other routines. See the Image Processing sample program for a live example.

OpenGL Websites

(from Dominic Curran's OPENGL-GAMEDEV-L post)

The Official OpenGL Site - News, downloads, tutorials, books & links:- http://www.opengl.org/

The archive for this mailing list can be found at:- http://www.egroups.com/list/opengl-gamedev-l/

The OpenGL GameDev FAQ:- http://www.rush3d.com/opengl/

The EFnet OpenGL FAQ:- http://www.geocities.com/SiliconValley/Park/5625/opengl/

The Omniverous Biped's FAQ:- http://www.sjbaker.org/steve/omniv

OpenGL 1.1 Reference - This is pretty much the Blue book on-line:- http://tc1.chemie.uni-bielefeld.de/doc/OpenGL/hp/Reference.html

Red Book online:- http://fly.cc.fer.hr/~unreal/theredbook/

Manual Pages:- http://pyopengl.sourceforge.net/documentation/manual/reference-GL.html

Information on the GLUT API:- http://www.opengl.org/developers/documentation/glut.html

The Mesa 3-D graphics library:- http://www.mesa3d.org

SGI OpenGL Sample Implementation (downloadable source):- http://oss.sgi.com/projects/ogl-sample/

OpenGL site with a focused on Delphi (+ OpenGL Hardware Registry):- http://www.delphi3d.net/

Game Tutorials - A number of OpenGL tutorials:- http://www.gametutorials.com/

Some nice OpenGL tutorials for beginners:- http://nehe.gamedev.net/

Humus - Some cool samples with code:- http://esprit.campus.luth.se/~humus/

Nate Robins OpenGL Page (some tutorials and code) http://www.xmission.com/~nate/opengl.html

Developer Sites for Apple, ATI & Nvidia:- http://developer.apple.com/opengl/ http://mirror.ati.com/developer/index.html http://developer.nvidia.com/

OpenGL Extension Registry:- http://oss.sgi.com/projects/ogl-sample/registry/

The Charter for this mailing list can be found at OpenGl GameDev Site:- http://www.geocities.com/SiliconValley/Hills/9956/OpenGL/

OpenGL Usenet groups:- news:comp.graphics.api.opengl

Scene Graphs

"Scene graphs" are a concept that has been essential to graphics since the 1960s, but for which the preferred design has changed radically. G3D uses a model of scenes designed for high performance under modern GPUs.

The terminology and structure is fairly standard in the field. The following is a brief introduction to modern scene graphs in general, with "in G3D" comments highlighting G3D-specific implementation or design elements.

A G3D::Scene contains global lighting information (typically "image based lighting"), metadata, and entities.

Entity

A G3D::Entity is an object in the scene that has a position in world space, a bounding box, and basic noun-like functionality. They are not necessarily visible. Popular categories/subclasses/specializations include camera, point light, visible entities, and trigger (aka marker) entities. Triggers/markers are invisible objects intended to trigger event handlers on collisions. In casual conversation, "entity" means "visible entity" and there would be some other modifier to specify one of the other cases...in code, it makes more sense to call the base class "entity" and have an explicit "visible" class.

Some entities are explicitly placed in world space and use C++ code or physical simulation for movement. Others have little domain-specific programs attached to them for animation. E.g., "follow this spline", or "rotate slowly". G3D calls this a "track", but there isn't any common name for it.

Parenting

An Entity can be "parented" (which should actually be referred to as "childed"; common terminology here is confusing). That is, it may have a parent entity and its track can be specified relative to that parent. An Entity may thus implicitly also have child entities. Children aren't always represented explicitly (and they aren't in G3D)...you have to work from children to parents and there is no back pointer.

The parent-child relationships form a tree. The G3D formulation is a little looser than explicit parent pointers. Instead of explicit parents, the track program can simply refer to other entities by name. At the beginning of simulation, the engine runs a topological sort based on dependencies detected in the parse trees of the the tracks, and then simulates entities in the correct order so that dependent entities are processed after the ones that they are dependent on. It won't hit an infinite loop even in the event of a cycle, however, since G3D::Scene only simulates each entity once per time step...if you make a circular dependency, it will be handled reasonably by having the entities chase each other across multiple frames.

Regardless of the program, the objects all store an explicit world space "frame" (G3D::CFrame). The animation/tree information is solely for recomputing the next world-space frame during simulation. Materials, scale, and other properties are not put into a 1980's-style "scene graph" tree in modern graphics programs at run time.

Visible Entities

A G3D::VisibleEntity has some visible representation attached to it that will be rendered. Since this representation must describe materials, character animations, and deformations as well as geometry, it is a fairly complex class. We call this a G3D::Model. It corresponds to something loaded from an FBX, OBJ, OFF, etc. file and represents all possible configurations of the visible representation. The most common G3D model subclass is G3D::ArticulatedModel. There are other special ones for terrain and other cases that have particular structure, and you can make your own.

Surfaces

To render, the visible entity combines a "Pose" (which is usually just a table of join positions) with a model to create a G3D::Surface. There isn't a generic pose base class because each Model subclass requires its own infromation. A Surface is the posed model...it contains [references to] vertex arrays, textures, and other data ready to be submitted to the GPU. In fact, once you have a Surface, you can discard the Entity and Model if you are rendering only a single frame (e.g., ray tracing still images).

A G3D::Renderer takes arrays of Surfaces, sorts and culls them, computes G3D::ShadowMaps, etc., and eventually issues some OpenGL commands via G3D::RenderDevice to make an image appear.

The "Universal" Classes

In G3D, the G3D::UniversalModel class works with G3D::UniversalSurface, G3D::UniversalMaterial, G3D::UniversalSurfel, and G3D::UniversalBSDF (these would likely be prefixed "common" in an editor or other engine, but we felt that the relatively-sophisticated material model we used wasn't very common!).

You can make your own G3D::Material, G3D::Surfel, and G3D::BSDF classes, although often it is easier to do some tricks with overriding the default shaders with modified versions in your program directory to achieve changes to the rendering algorithms. None of these Universal- classes are required by the main rendering abstraction. Instead, these are details of how a specific Surface subclass creates its own sub-abstractions for implementing the Surface interface.

Design

While this abstraction favors rasterization on modern GPUs, there are some non-rasterization classes that also leverage them. For example, G3D::TriTree accepts Surface arrays and then allows you to cast rays at them, and the G3D::Surfel classes abstract CPU material sampling and light scattering.

G3D allows you to mix your own subclasses with the standard ones, and to replace or discard any pieces of this abstraction that you don't wish to use. For example, you might write a real-time ray tracing G3D::Renderer subclass, could subclass G3D::DefaultRenderer to implement exponential-variance shadow maps, or could make a subdivision surface Surface subclass.

The intent of this design is twofold. First, it provides modularity so that changes so that different rendering and modeling concepts are isolated. E.g., the thing that does transparency rendering doesn't have to know about or depend on the things that do animation or represent materials. Second (and as a result of the first point), you can bring the full power and quality of a complete engine to your projects, while only having to implement the individual algorithms for narrow parts of modeling, rendering, and animation.

I've used G3D for prototyping pieces of new commercial video games and hundreds of research papers and projects. My code for each prototype was typically a few hundred lines. While G3D's classes and concepts follow standard practice, many of G3D's specific APIs evolved in response to flexibility needed across of those experiences. Some of the more "ninja" features, like arbitrary shader uniform variables on poses and shader macro arguments, are unlikely to be used in a typical student project and a little tricky to understand...but if you reach the point where you need them, then they will suddenly make sense to you.

Contents

Contents

1.8.15

1.8.15